Page 85 - Koderman, Miha, and Vuk Tvrtko Opačić. Eds. 2020. Challenges of tourism development in protected areas of Croatia and Slovenia. Koper, Zagreb: University of Primorska Press, Croatian Geographical Society

P. 85

tourism in protected areas and the transformation of mljet island, croatia

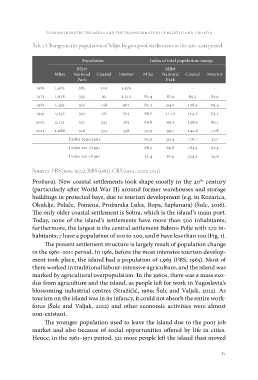

Tab. 2 Changes in the population of Mljet by groups of settlements in the 1961–2011 period

Population Index of total population change

Mljet Mljet Coastal Interior Mljet Mljet Coastal Interior

National National

1,479

Park 1,211 Park

962

1961 1,963 381 103 703 ----

1971 563

1981 1,638 335 92 438 83.4 87.9 89.3 81.9

1991

2001 1,395 315 118 85.2 94.0 128.3 79.4

2011

1,237 352 182 88.7 111.7 154.2 73.1

1,111 317 231 89.8 90.1 126.9 80.1

1,088 316 334 97.9 99.7 144.6 77.8

Index 1991/1961 63.0 92.4 176.7 47.5

Index 2011/1991 88.0 89.8 183.5 62.3

Index 2011/1961 55.4 82.9 324.3 29.6

Sources: FBS (1965; 1972); RBS (1983); CBS (1994; 2003; 2013)

Prožura). New coastal settlements took shape mostly in the 20th century

(particularly after World War II) around former warehouses and storage

buildings in protected bays, due to tourism development (e.g. in Kozarica,

Okuklje, Polače, Pomena, Prožurska Luka, Ropa, Saplunara) (Šulc, 2016).

The only older coastal settlement is Sobra, which is the island’s main port.

Today, none of the island’s settlements have more than 500 inhabitants;

furthermore, the largest is the central settlement Babino Polje with 270 in-

habitants; 7 have a population of 100 to 200, and 6 have less than 100 (Fig. 1).

The present settlement structure is largely result of population change

in the 1961–2011 period. In 1961, before the most intensive tourism develop-

ment took place, the island had a population of 1,963 (FBS, 1965). Most of

them worked in traditional labour-intensive agriculture, and the island was

marked by agricultural overpopulation. In the 1960s, there was a mass exo-

dus from agriculture and the island, as people left for work in Yugoslavia’s

blossoming industrial centres (Stražičić, 1969; Šulc and Valjak, 2012). As

tourism on the island was in its infancy, it could not absorb the entire work-

force (Šulc and Valjak, 2012) and other economic activities were almost

non-existant.

The younger population used to leave the island due to the poor job

market and also because of social opportunities offered by life in cities.

Hence, in the 1961–1971 period, 321 more people left the island than moved

83

Tab. 2 Changes in the population of Mljet by groups of settlements in the 1961–2011 period

Population Index of total population change

Mljet Mljet Coastal Interior Mljet Mljet Coastal Interior

National National

1,479

Park 1,211 Park

962

1961 1,963 381 103 703 ----

1971 563

1981 1,638 335 92 438 83.4 87.9 89.3 81.9

1991

2001 1,395 315 118 85.2 94.0 128.3 79.4

2011

1,237 352 182 88.7 111.7 154.2 73.1

1,111 317 231 89.8 90.1 126.9 80.1

1,088 316 334 97.9 99.7 144.6 77.8

Index 1991/1961 63.0 92.4 176.7 47.5

Index 2011/1991 88.0 89.8 183.5 62.3

Index 2011/1961 55.4 82.9 324.3 29.6

Sources: FBS (1965; 1972); RBS (1983); CBS (1994; 2003; 2013)

Prožura). New coastal settlements took shape mostly in the 20th century

(particularly after World War II) around former warehouses and storage

buildings in protected bays, due to tourism development (e.g. in Kozarica,

Okuklje, Polače, Pomena, Prožurska Luka, Ropa, Saplunara) (Šulc, 2016).

The only older coastal settlement is Sobra, which is the island’s main port.

Today, none of the island’s settlements have more than 500 inhabitants;

furthermore, the largest is the central settlement Babino Polje with 270 in-

habitants; 7 have a population of 100 to 200, and 6 have less than 100 (Fig. 1).

The present settlement structure is largely result of population change

in the 1961–2011 period. In 1961, before the most intensive tourism develop-

ment took place, the island had a population of 1,963 (FBS, 1965). Most of

them worked in traditional labour-intensive agriculture, and the island was

marked by agricultural overpopulation. In the 1960s, there was a mass exo-

dus from agriculture and the island, as people left for work in Yugoslavia’s

blossoming industrial centres (Stražičić, 1969; Šulc and Valjak, 2012). As

tourism on the island was in its infancy, it could not absorb the entire work-

force (Šulc and Valjak, 2012) and other economic activities were almost

non-existant.

The younger population used to leave the island due to the poor job

market and also because of social opportunities offered by life in cities.

Hence, in the 1961–1971 period, 321 more people left the island than moved

83